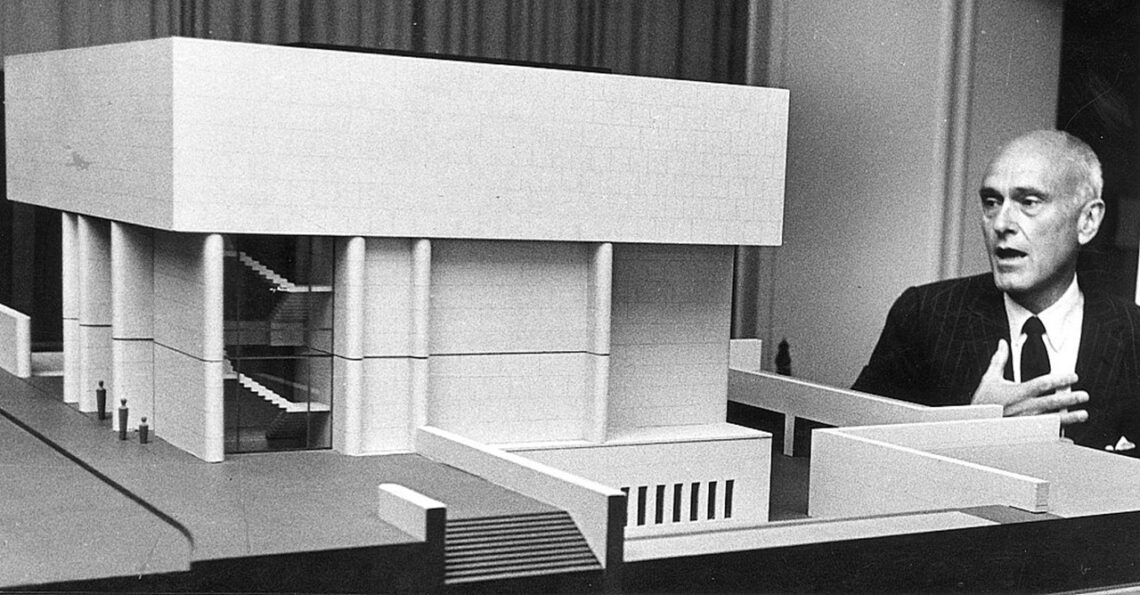

Philip Johnson’s Bielefeld Art Gallery from 1968:

a challenge for German architectural criticism.

A contribution by Prof. Dr. Fritz Neumeyer

emeritus Professsor for architectural theory at the Technical University Berlin

Keynote speech in the framework of the symposium

Yesterday. Today! Tomorrow?

From the museum of late modernism, its history and its future, monument protection, the “third place” or climate box versus climate crisis.

Part I, April 21 + 22, 2023

Good Spirits, Bad Spirits: Facing the Stories of the Kunsthalle

The construction of the Bielefeld Kunsthalle presented German architectural critics with a challenge. Its outwardly closed, cube-shaped form did not correspond to the understanding of modern architecture at the time and evoked unpleasant memories of the architectural formal language of totalitarian regimes in the first half of the 20th century. However, the Bielefeld building clearly illustrates the change in modern architecture in the 1960s. When the u.s. architect Philip Johnson was commissioned to design the Bielefeld Kunsthalle, he had long since bid farewell to the International Style and was now undertaking an architectural reorientation that called for more design freedom and thus anticipated postmodernism by more than a decade. In his lecture, Professor Fritz Neumeyer gives many international examples to explain the development of Philip Johnson’s architecture.

The architectural appearance of Philip Johnson’s Bielefeld Kunsthalle is characterized by cubic compactness and structural openness at the same time. This ambivalence posed a challenge to architectural criticism in this country in 1968. While the spatial organization, lighting, and orientation of the interior were praised, the exterior appearance was largely met with incomprehension and negativity because it clearly did not correspond to the prevailing understanding of modern architecture in German architectural perception at the time. This already concerned the fact that the building structure, which was made of reinforced concrete, was clad with red sandstone – in contrast to the modern exposed concrete construction method of the time. The semi-columnar rounded corners of the wall panes and the heavy-weight closed volume of the upper museum rooms, lit only by skylights, awakened in critics unpleasant memories of architectural monumentalism in the force of expression. Thus, Johnson’s Bielefeld Museum was stylized by the press in 1968, among other things, alternately as a “bunker building” (Der Spiegel), a “fortress” (FAZ), “a mixture of water tower, mausoleum, and paperweight” (Bauwelt). In the face of these polemics, the architectural historian Wolfgang Pehnt correctly summed up in 1970 in the volume Neue Deutsche Architektur that Johnson’s museum had been condemned by critics “in Germany as a monstrous curiosity that one did not know how to place in any context.”

The fact that the contexts in the world of modern architecture had been in flux since the late 1950s was hardly noticed in this country. In terms of architectural history, the Kunsthalle Bielefeld is a unique testimony to the changes in modern architecture in the 1960s on German soil. The International Style – to which the Bielefeld building is sometimes still attributed today – had long since been abandoned by its co-founder in 1932, when he was commissioned to build the Kunsthalle. Johnson now undertook an architectural reorientation that called for greater design freedom through an unbiased approach to architectural history and individual expression, thus anticipating postmodernism by more than a decade.

You can watch the recording of the entire talk here.

Dr.-Ing. Architect, 1993-2012 Professor of Architectural Theory at the Technical University of Berlin. 1992 Jean Labatut Professor, School of Architecture, Princeton University. 1989-1992 Professor of Architectural History, University of Dortmund. – Visiting professorships at Harvard University, KU Leuven, SCIARC, Institut d’ Humanitats de Barcelona, Universidad de Navarra, Pamplona.

Numerous publications on the theory and history of architecture, including: Mies van der Rohe. The artless word. Gedanken zur Baukunst, Berlin 1986, 2nd ed. 2016; Friedrich Gilly 1772-1800. Essays on Architecture, Santa Monica 1994 (Berlin 1997); Der Klang der Steine. Nietzsches Architekturen, Berlin 2001; Quellentexte zur Architekturtheorie, Munich 2002; Originalton Mies van der Rohe. Die Lohan-Tapes von 1969, Berlin 2020; Ausgebootet: Mies van der Rohe und das Bauhaus 1933 – Outside The Bauhaus. Mies van der Rohe and Berlin 1933, Berlin 2020.

The symposium is sponsored and supported by:

Gallerie