Viewpoints

View into the collection #7

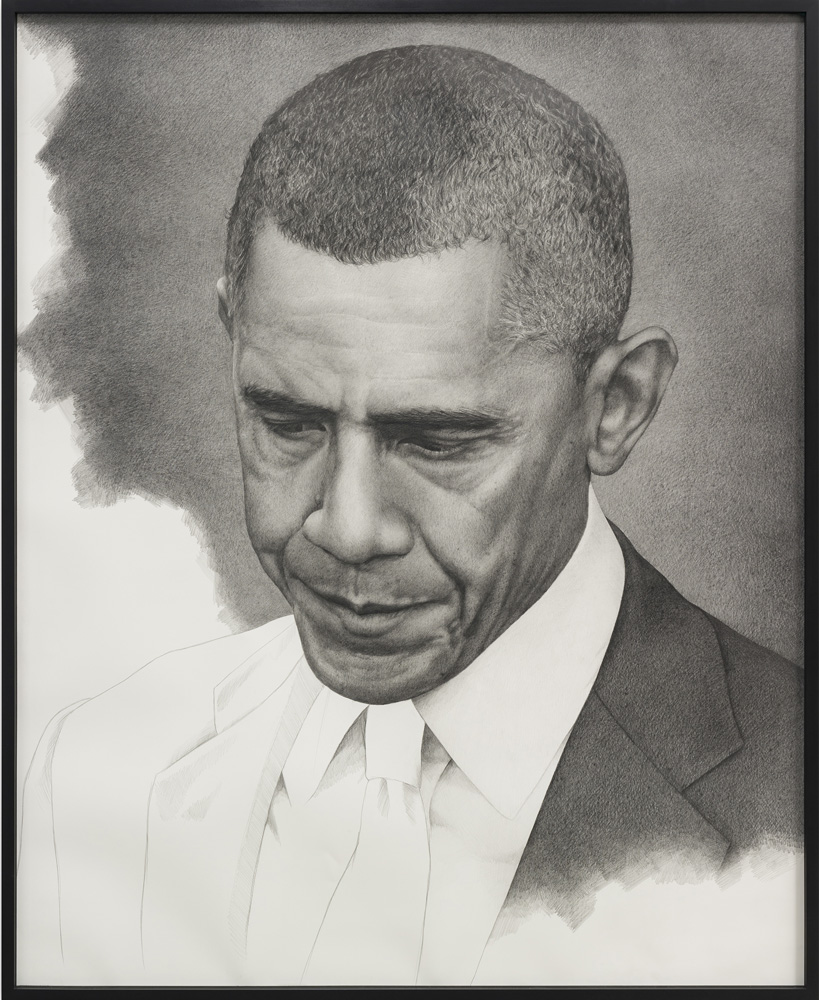

Taking Käthe Kollwitz’ and Mona Hatoum’s works as a starting point, we take a new look at the Kunsthalle Bielefeld’s collection and present works that can be read as points of view. What they have in common is that they are resistant to the status quo. Counter-images of the here and now are juxtaposed with works that directly criticize the current situation. The question of how we adopt positions in the media age will also be discussed.

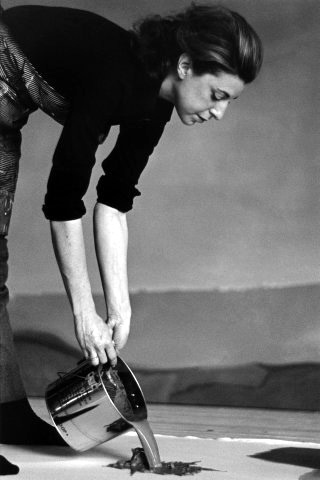

With Georg Baselitz, Max Beckmann, Monica Bonvicini, Karl Haendel, Robert Longo, Otto Mueller, Emil Nolde, Germaine Richier, Katharina Sieverding and others.