Architecture

Between modernity and postmodernity

The building

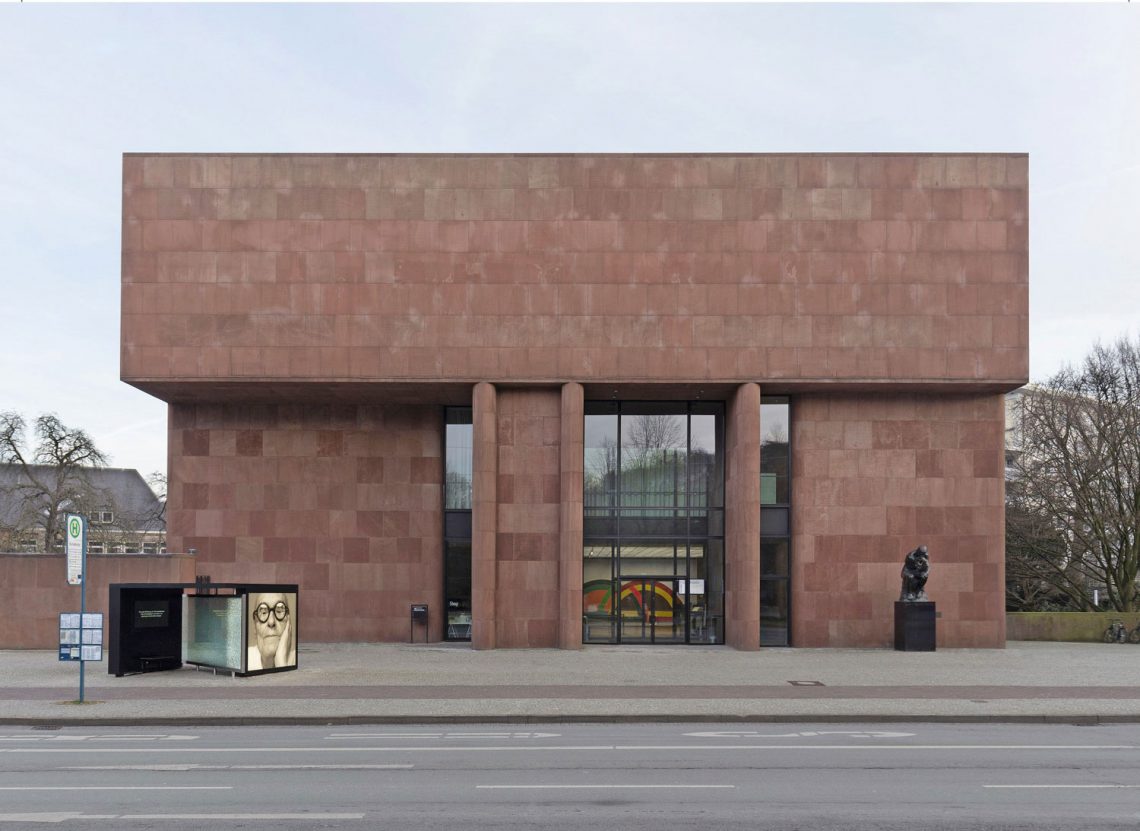

The Kunsthalle Bielefeld was built in 1968 according to the plans of the US-American architect Philip Johnson (1906-2005). It is his only museums building in Europe and a monument of architectural history. The iconic building marks Johnson’s first early turning point toward a postmodern formal language.

The wide window fronts and open floor plan with recessed wall panels still reflect the Modernist and “International Style” principles of the 1920s and 30s. Johnson coined this term as a theorist along with architectural historian Henry-Russell Hitchcock.

The cubic museum building made of red Main sandstone is full of tension: Compact forms alternate with open vistas. The massive upper part of the building rests on a structure of semicircularly closed wall panels and asymmetrically arranged half-columns. With the help of these elements, Johnson still adhered to the cuboid building with smooth surfaces typical of modernism, but at the same time introduced more sculptural building structures.

From the open floor plan to the democratization of art

The open floor plan with spaces flowing into one another creates diverse, ever-changing visual axes. Principles such as permeability, connection and dialogue are thus emphasized. The strong reference to the outside through numerous large window fronts facing the city and the public sculpture park also conveys openness and transparency. It also allows for steady movement.

With an exhibition area of about 1,200sqm, the building comprises three above-ground and two underground floors. The entrance hall with café and adjacent space for art education as well as the first and second exhibition floors are above ground. The lower floors contain a film and lecture hall, a library open to the public, and the administration offices, which are accessed through a foyer.

With its design by Philip Johnson, the Kunsthalle Bielefeld was one of the first new museum buildings in the then still young Federal Republic. The new building was made possible in large part by a generous donation from the family of Rudolf-August Oetker, who, together with the then director Joachim Wolfgang von Moltke, was able to win Johnson for the project.

With the open spatial organization of the exhibition areas, which do not impose a clear sequence on the visitor during the tour, and the introduction of a room for pedagogy, which was revolutionary in Germany at the time, the house stands for the idea of a “democratization of art” in the 1960s.

The architect

Philip Johnson (1906-2005) was a U.S. architect, architecture critic, and co-founder of the Department of Architecture and Design at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York. He served in various capacities at MoMA from 1932-1988: as director of the department (between 1932-34 and 1949-1954) and as curator. In the capacity of trustee and patron, he enabled MoMA to make numerous acquisitions throughout his life and donated important works from his own collection to the museum. His publication, co-authored with Henry-Russell Hitchcock, The International Style: Architecture Since 1922 (1932) was concept-forming.

As an architect, Johnson not only participated in several epochal changes like few others, but played a significant role in shaping them, taking an authoritative role in the discourse of modernism and late modernism as well as postmodernism. His Glass House (1947-49) in New Canaan was his first international breakthrough; in 1953 he was responsible for the Sculpture Garden at MoMA; with the “AT&T Building,” New York (1980-84) or the “Lipstick Building,” New York (1986), he created iconic works of postmodernism.

Controversy about Philip Johnson

Impressed by the Nazi regime in Germany, which he had witnessed in the form of parades and marches on several trips through Europe, Johnson quit his job at MoMA in 1934 with the vision of himself becoming minister of culture in a government led by U.S. right-wing populists under Huey Long. Johnson was involved in pushing fascist developments in the U.S. through the publication of essays. Also, as late as 1938, during a trip to Poland, he provided the German Reich with information about the state of the Polish army. His shift from art to politics was publicly noted; in 1940, his presence in the environment of U.S. fascists was illustrated in a long article in Harper’s Magazine; in the 1941 bestseller Berlin Diary (William Shirer), he was described as an “American fascist” and collaborator. He was monitored and questioned by the FBI, but unlike companions at the time, Johnson was never arrested or charged.

Subsequently, Johnson abruptly changed course and devoted himself to the in-depth study of architecture at the Graduate School of Design, Harvard University. In 1947 he returned to the architecture department at MoMA. His political past has haunted him throughout his life; in the 1990s, he admitted it in a radio interview as an “unforgivable personal lapse.”

After Marc Wortman’s (2016) reappraisal of Johnson’s political past, the “Johnson Study Group,” an association of architects and cultural workers, formed around “Black Lives Matter” and called on MoMA to abandon the naming of some galleries after Philip Johnson, which had been introduced in 1984. Since then, there has been debate about the proper handling of Philip Johnson’s legacy. Harvard University has renamed the “Philip Johnson Thesis House,” a building constructed by Johnson while he was a student, “9 Ash Street.”

In Bielefeld, the sculpture “Bus Shelter XII. Shattered Glass / The Confessions of Philip Johnson” by Dennis Adams stands in front of the Kunsthalle since 2018. In it, Adams critically examines Johnson’s ambivalent personality. Dennis Adams has put around 500 “confessions” into the architect’s mouth, which are played back on two screens.

For more on Philip Johnson, see our references at the end of the text.

Controversy over the naming of the Kunsthalle

When it opened in 1968, the museum was called “Richard-Kaselowsky-Haus. Kunsthalle Bielefeld”. With this naming, Rudolf-August Oetker, the founder of the Kunsthalle, honored his stepfather Richard Kaselowsky. Throughout his life, the latter had been committed to culture in the city of Bielefeld. However, Kaselowsky was also a member of the NSDAP and a member and donor in the “Heinrich Himmler Circle of Friends”, a strategic network between business and the regime.

Against this background, the naming led to protests even before the opening and to the cancellation of the ceremonial inauguration on September 27, 1968.

In the years that followed, the debate about the naming of the Kunsthalle Bielefeld flared up again and again, accompanied by civil society protests, actions, artistic interventions, and political events by students, artists, academics, and committed citizens of the city’s society. 1985 wurde eine Umbenennung der Kunsthalle in „Käthe-Kollwitz-Haus“ gefordert. After almost 30 years, the Bielefeld City Council decided to remove the controversial name in 1998. The dedication plaque in the entrance area of the Kunsthalle from 1968 was replaced by a text in which Richard Kaselowsky is no longer mentioned by name due to another council decision in August 2017.

General renovation and extension

The listed building of the Kunsthalle Bielefeld will undergo a comprehensive general refurbishment and extension from mid-2025. The museum takes this opportunity to discuss the history of the house, including its controversies, in depth according to the current state of research. The upcoming transformation process offers the opportunity to make adjustments to current and future exhibition requirements and to overhaul the museum’s infrastructure from an ecological point of view.

A three-part symposium in 2023 will create initial starting points for a critical examination of the Kunsthalle’s history and architecture as well as its transformation.

The Kunsthalle Bielefeld is part of the architecture route art museums.

References to Philip Johnson:

- https://www.vanityfair.com/culture/2016/04/philip-johnson-nazi-architect-marc-wortman

- Schulze, Franz: Philip Johnson. Life and Work. Springer Verlag 1996.

- Lamster, Mark: The Man in the Glass House. Philip Johnson, Architect of the Modern Century. Little, Brown and Company 2018.

- Wortman, Marc: Fighting the Shadow War. A Divided America in a World at War. Atlantic Monthly Press, 2016

Gallerie