Taking a stand. Käthe Kollwitz, Mona Hatoum

“Taking a stand” is more important than ever in today’s society – at a time characterised by worsening social inequalities, growing hostility towards those who think differently, increased experiences of flight and migration, conflict and war. The exhibition brings together two artists, Käthe Kollwitz and Mona Hatoum – one historical and one contemporary – whose art serves as a memorial against suffering and oppression and stands for greater humanity.

“I want to have an impact in this time” is one of the most famous statements by Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945). Like few others, she linked her art with a sociopolitical, humanitarian and pacifist commitment. With empathy, she took on the people oppressed by poverty and misery due to industrialisation, rural exodus and unemployment at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. Kollwitz’ experiences of two world wars and their consequences, including the loss of her own son who fell in 1914, are also reflected in her work.

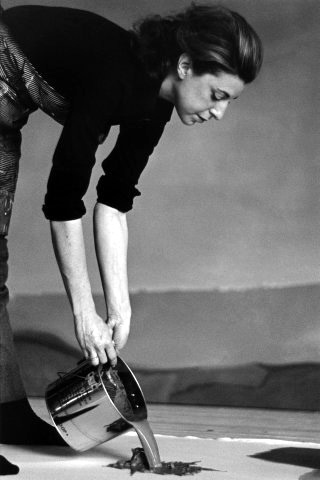

The works of Beirut-born artist Mona Hatoum (*1952, lives in London), who was on a short visit to London in 1975 when the outbreak of the Lebanese Civil War prevented her from returning home, adds a global perspective to the exhibition. Like Kollwitz, Hatoum, winner of the 2010 Käthe Kollwitz Prize, also addresses basic human experiences. Pain, suffering and vulnerability, but also the familiar and domestic, which is destroyed, endangered or alienated by institutional violence and systems of power, are central to her work.

Despite their subject matter, the works of both artists, who share the strategy of using a formal language reduced to the essentials and use colour in a pointed manner at best, are not an expression of resignation. The works of both artists appeal to our compassion and testify to positive commitment.

An exhibition in cooperation with the Kunsthaus Zürich, in collaboration with the Käthe Kollwitz Museum Köln.

The exhibition is sponsored by the Kulturstiftung pro Bielefeld and the Förderkreis Kunsthalle Bielefeld e.V.

The education and communication of the exhibition is sponsored by Sparkasse Bielefeld.

Gallerie