The passions of Philip Johnson

A contribution by Prof. Dr. Jeffrey Lieber

Professor of Art History at Texas State University.

Impulse lecture within the framework of the symposium

Yesterday. Today! Tomorrow?

From the museum of late modernism, its history and its future, monument protection, the “third place” or climate box versus climate crisis.

Part I, April 21 + 22, 2023

Good Spirits, Bad Spirits: Facing the Stories of the Kunsthalle

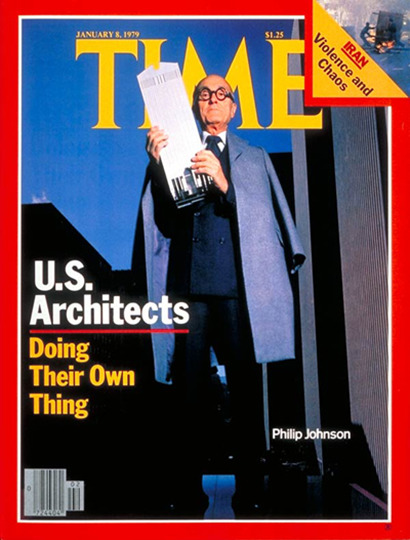

The Passions of Philip Johnson

Are there new conclusions to be drawn from the life and work of a figure about whom so much has already been written? Since his death in 2005 at the age of 98, historians have parsed the myths Johnson cultivated for himself during his long life and gauged his impact on the development of modern and contemporary architecture. Analyses of Johnson’s life and work sometimes devolve into stereotypes. He has been accused of stylistic promiscuity, labeled effete and narcissistic, and depicted as a high-strung nihilist and destructive cynic who disdained normative social and political values. The extent of Johnson’s fascist activities in the 1930s is by now well-documented. Many historians argue that Johnson distanced himself from politics in the 1950s and 1960s to rehabilitate his reputation and have not found much in the way of political content in his work, although he seemingly embraced the dictates of corporate capitalism in his later postmodern projects. These issues raise several questions, which Lieber addresses in his talk: What happened to Johnson’s political passions after 1940, when, at the age of 34, he abandoned political activism and enrolled at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design? Throughout the post-WWII decades, Johnson often spoke about his “passion for history.” How did he deploy this passion in his writings and to what ends? How did Johnson dramatize his ideas about beauty and history in the pavilions he built on his New Canaan estate and in his museum designs of the 1950s and 1960s and were these projects part of an oppositional approach?

You can watch the recording of the entire talk here.

Jeffrey Lieber is Associate Professor of Art History at Texas State University and the author of Flintstone Modernism or the Crisis in Postwar American Culture (MIT Press, 2018). His essays on Philip Johnson have appeared in international publications, including the Neue Zürcher Zeitung. Lieber’s 2018 opinion piece in The New York Times (“What Will We Lose When the Union Carbide Building Falls?”) sparked a debate about the importance of mid-20th century architecture in the United States. His wide-ranging interests in the field have been sponsored by the Delmas Foundation Grant for Independent Research in Venice to cite one example, and are reflected in his curation of provocative film series for the Harvard Film Archive and The New School in New York. He received his AB from Vassar College and his PhD in art history from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

The symposium is sponsored and supported by:

Gallerie