Oscar Tuazon

What we need

Press Download

Press release

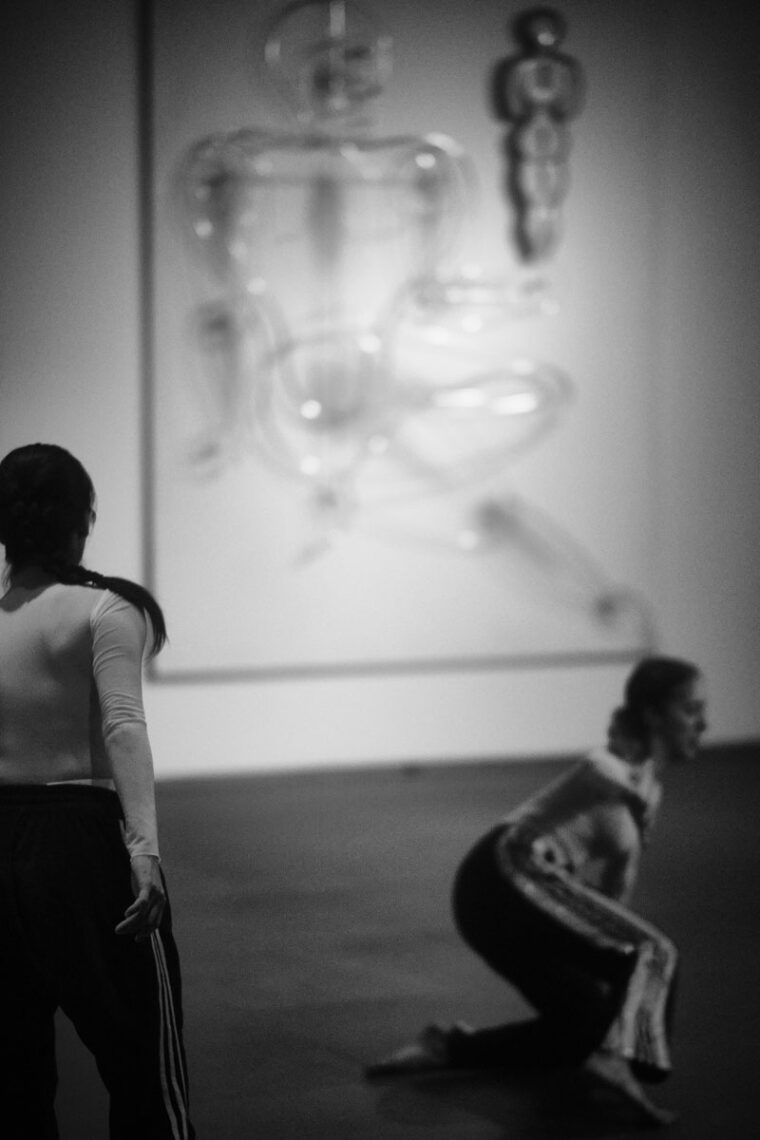

Oscar Tuazon’s (*1975) artistic practice is guided by intuitive choices and processual work. The US artist works with natural and industrial materials to create objects, structures and installations that can be used, occupied or otherwise engaged by viewers. His works are rooted in minimalism, conceptual art, 20th century architectural history, and the technique of do-it-yourself and bricolage, in which artworks are constructed from materials available in the environment. His works are thus closely related to the social and physical space surrounding them and to the audience, which becomes an active part of many works and processes.

Together with Bergen Kunsthall and Kunst Museum Winterthur, Kunsthalle Bielefeld presents a trio of exhibitions that approach Oscar Tuazon’s work in different ways. The three individual projects form an overarching unity and thus provide a multifaceted overview of Tuazon’s artistic oeuvre. The Kunsthalle will show a cross-section of Tuazon’s work from the last ten years to the present day and thematically address questions about artistic and social existential needs: What is absolutely necessary, indispensable and systemically relevant? What are our essential needs?

“Oscar Tuazon. What we need” is, after “Aurel Dahlgrün. Summit” the second epilogue to the exhibition “Following the Water” (2022), which concludes the project.

Oscar Tuazon was inspired by the Johnson model for his work “Garden for Maria Mies” and designed his own version of the Kunsthalle on the same scale especially for the exhibition. The Kunsthalle, which is a listed building, is due to undergo a comprehensive general refurbishment and extension from mid-2025. Tuazon’s “Garden for Maria Mies” is at the same time a homage to the sociologist Maria Mies and something like an “unofficial”, artistically free design draft for the Kunsthalle extension.

If you want to learn more about Maria Mies and her ideas, approaches and theories, you can find more information in the text below. Or feel free to browse the books we’ve gathered for you in Tuazon’s “Reading Booth.”

Who was Maria Mies?

Until her death in May 2023, Maria Mies was a driving force of feminist activism through her research since the 1970s. The 1983 book “Frauen, die letzte Kolonie: Zur Hausfrauisierung von Arbeit” (Women, the Last Colony: On the Homemaking of Work), which Maria Mies published together with her Bielefeld colleagues Claudia von Werlhof and Veronika Bennholdt-Thomsen, laid the foundation for the so-called “Bielefeld Approach.” This feminist materialist theory engages with the ideas of Marxism and criticizes, among other things, women’s unpaid domestic work. With Indian activist Vandhana Shiva, Maria Mies wrote the book “Ecofeminism – the Liberation of Women, Nature and Oppressed Peoples.” With this, too, the scientist underlined her commitment against militarism and for emancipation and solidarity with the exploited and oppressed people worldwide.

In the preface of “Ecofeminism” Maria Mies writes: “The patriarchal-capitalist system has built its rule from the beginning on the exploitation and subjugation of nature, foreign lands and women. Nature, women and foreign lands are the colonies of this system to this day. The aim of this colonization is to gain unlimited power of an elite over everything living and inanimate. Without the exploitation and subjugation of these colonies, modern industrial society would not exist.”

You can find more information about her life and a foto of Maria Mies here: https://www.fritz-bauer-forum.de/datenbank/maria-mies/

Audio by: Charlotte-Sophie Laege

Recording and editing in cooperation with the Making Media Space in the Digital Learning Lab at Bielefeld University.

As soon as you entered the Kunsthalle, you surely saw Frank Stella’s painting, over seven meters wide, with its colorful stripes and patches of color. It is called “Khurasan Gate I” and is from 1968. If you look at the picture from the side, you will notice a peculiarity: The canvas is not flat, but clearly protrudes into the room. Stella experimented with specially made stretcher frames for this purpose, overcoming the “classic” rectangular canvas format in the 1960s. These works are called “shaped canvases”. “Khurasan Gate I” is a particularly impressive example of how artists* in the 1960s developed the traditional canvas painting into an independent pictorial object.

The form of a double arch emphasized in Stella’s “Khurasan Gate I” meets a room-sized work by Oscar Tuazon in the entrance area of the Kunsthalle. Calmly walk closer to the wooden structure that builds up in front of the Stella. You can go around them or through the openings between the four vertical and three horizontal beams. Tuazon’s work, “Where I Lived and What I Lived For,” recalls makeshift structures for survival, such as beams in mine shafts. Have you noticed how the construction shifts in front of Stella’s painting, depending on the angle and point of view, disrupting or changing the view of it?

This interweaving of the two works by Stella and Tuazon kicks off and demonstrates the relationship between the exhibitions “What We Need” and “Need and Have”: a close connection in terms of content and form between works by Tuazon and works from our collection, through which new perspectives on both are made possible.

Painting in the 1960s

At that time there was always talk of the “end of painting”. This was due, on the one hand, to the many new possibilities that challenged painting’s dominance. Since the 1920s, photography and film have also been used as an artistic medium. The 1960s saw the addition of performance, which used the artist’s own body as a means of expression, and conceptual art, in which the idea for a work was more important than its realization. The first installation works were also created, in which artists filled entire rooms with different objects. For European artists, the experiences of the Second World War and the Shoah added to this: terrible events that for some could no longer be depicted with traditional painting – they sought new possibilities. When they decided to continue painting, they often broke up the classical picture format. In addition to Stella’s work in the entrance hall, examples of this can be seen primarily on the second floor.

“What does the title “Khurasan Gate I” mean?”

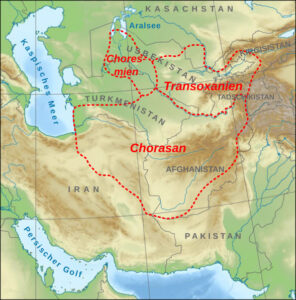

“Gate” means “gate” in German. Stella thus refers to architecture, underscoring the expansive character of his art. The title also contains the word “Khurasan”. It is the historical name of an area in what is now Afghanistan and eastern Iran. Whether Stella refers to a specific gate, for example in a city wall, or whether the name was chosen more or less at random, has not been conclusively determined.

Image: Lencer, Map Chorasan-Transoxania-Choresmia, CC BY-SA 3.0

Audio by: Matthias Albrecht

Recording and editing in cooperation with the Making Media Space in the Digital Learning Lab at Bielefeld University.

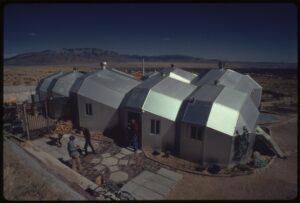

Photographer: Norton, Boyd

Via wikimedia.org, no known copyright restrictions

Tuazon’s work “Substitute” is reminiscent of a window, double-glazed and fixed in a steel frame. Behind this window is mounted an oil drum, which is connected to the framed glass panes by a structure of pump bottle and pipe. In the cavity between the panes, Tuazon has pumped polystyrene, better known as Styrofoam, in liquid form at high pressure. Do you have any idea how much force had to be put into it? We can no longer see the filling itself, but we can see the traces it left behind

“Substitute” means “replacement” in German. What might the construction seen here be a substitute for? By filling the otherwise easily overlooked space, the artist makes it visible. Could the Styrofoam, with its heat insulating property, be a substitute for the gas normally used to insulate a window?

What inspired Tuazon to create this work?

The work is based on Steve and Holly Baer’s “Zome House” in the New Mexico desert. They built it in 1971, over 50 years ago. The special thing about this house was that it was already heated with solar energy. How did that work? The couple built a water tank wall. It consisted of a glass pane behind which were several dozen oil drums filled with water. They warmed up during the day and released the heat into the interior of the building at night. Tuazon’s “Water Schools” are also based on the structure of the “Zome House”. You can see two of them in our exhibition.

More pictures also of the interior of the Zome House and an interview with the 1973 couple can be found at: motherearthnews.com

Audio by: Charlotte-Sophie Laege

Recording and editing in cooperation with the Making Media Space in the Digital Learning Lab at Bielefeld University.

Oscar Tuazon incorporates into his artistic work ideas from the history of art from the 1960s to the present day. This is especially true for Minimal Art. Works from the mid-1960s to 2022 are gathered in this room. Let’s take a look at what Tuazon’s 2016 “Reading Booth” has in common with them.

Let’s start with the fluorescent tubes that create this special lighting atmosphere. They are commercially available fluorescent tubes of standard size, shape and color. What happens as a result of Dan Flavin choosing them as his artistic material? He detaches them from their everyday use and transfers them to a new meaning as an object of contemporary art. This approach is typical of Minimal Art. Tuazon also illuminates his reading booth with fluorescent light and built it out of commercially available materials such as acrylic or aluminum. In addition to the material, light itself is also part of the artwork in Flavin’s work. Let it have an effect on you. What mood does the light create in the room, how do its rays illuminate the other works?

Minimal Art is therefore no longer necessarily a two-dimensional image, but extends into space, just as Charlotte Posenenske’s yellow steel elements literally do. The original version of the work was created between 1966 and 68, but the artist leaves it up to the exhibition organizers to decide how the individual parts are arranged, i.e. how the relief will actually look in the museum. Because Minimal Art doesn’t want to give us a set story or message, but an aesthetic effect. It is about the interactions between object, the surrounding space and us as viewers. With Tuazon’s Reading Booth you can experience this quite actively. If you go closer to the construction and look inside: Does the small space seem constricting or yet cozy inviting? Feel free to sit inside and literally look at the rest of the room from a new perspective.

There is one work in the room we haven’t talked about yet: Franziska Reinbothe’s “Untitled”. She has covered her canvas with chiffon and yarn, so that we can see through the surface the material substructure of painting This skeleton of the picture support forms a grid from several squares. This reduction to repeating basic geometric structures is another typical design principle of Minimal Art. The exterior impression of Tuazon’s reading booth is also determined by geometric forms.

Commercially available materials, interaction between space, art object, and you as the viewer, and geometric shapes: If you’re on the lookout for it, you’ll notice Minimal Art influences again and again elsewhere in the exhibition.

More about Dan Flavin’s work owned by Kunsthalle

For most of his career, US minimalist Dan Flavin was concerned with the artistic possibilities of fluorescent light. This work was created for a special occasion, just three years before the death of the artist, who was born in New York in 1933. In 1993, Galerie Annemarie Verna celebrated the inauguration of new gallery premises at Neptunstrasse 42 in Zurich. For this, Flavin developed a group of works that illuminated the rooms of the first exhibition there. That is why the subtitle of “Untitled” bears the dedication “For the Vernas on opening anew”.

Posenenske’s “Relief” – Between Reproduction and Prototype

Charlotte Posenenske was one of the few artists in Germany who absorbed the impulses of US Minimal Art at an early stage. The “reliefs” thematize the transition from surface to space. The elements can be combined into one shape or presented in series. Posenenske had them industrially produced as an unlimited series, unsigned. They were painted with weatherproof paint and sold at the production price. Since they continued to be reproduced after the artist’s death in 1985, all previously produced copies are considered “prototypes.” The work from our collection is not a “prototype”. It belongs to the “C series”, which consists of elements of the same shape type.

Audio by: Nadine Kleinken

Recording and editing in cooperation with the Making Media Space in the Digital Learning Lab at Bielefeld University.

About wikimedia.org, Creative Commons Zero

About wikimedia.org, Creative Commons Zero

Here you can see a work of the German-American artist Jimmy Ernst, the son of the famous surrealist Max Ernst.

Discover how many dark lines create tree-like structures in the image? Or how some of the lines form symbols? They belong to a sign system of their own. During his apprenticeship as a typesetter, Jimmy Ernst was fascinated by signs and symbols from all over the world. Among other things, he worked intensively on Chinese and Arabic character systems, cuneiform script, and also scripts of indigenous groups. This enthusiasm is reflected in the present work.

What do the structures in the background remind you of? Perhaps to a window front with shattered glass panes?

Pretty depressing, don’t you think?

This effect fits the title: “Thoughts on November 63,” which refers to the assassination of former U.S. President John F. Kennedy, who was shot in Dallas in November 1963.

On the free-standing wall on the far right you will see a work by the French painter and sculptor Louis Cane. Vertical and diagonal bars that repeatedly overlap. Colors and shapes overlay each other. What effect does this have? Do you get the impression of spatial depth?

This is the effect both artists, Jimmy Ernst and Louis Cane, strive for. Through colors, shapes, superimpositions and the play with light and dark, they achieve spatial impressions.

The two works are juxtaposed by Oscar Tuazon’s work “Building.” Depending on your point of view and vantage point, the timbers of the framework overlap to varying degrees, just like the color bars and lines in the works of Ernst and Cane. And the window front in Jimmy Ernst’s work shows an engagement with architecture, as is also evident in Oscar Tuazon’s work.

Audio by: Matthias Albrecht

Recording and editing in cooperation with the Making Media Space in the Digital Learning Lab at Bielefeld University.

In this space the question is asked: How can painting connect with the space in which it is seen?

Have you noticed the damaged canvas yet? Lucio Fontana cut the flat surface to open the canvas into the real space behind it. There’s not much room, you might object, but a connection is made.

Günther Uecker also works on the image carrier. He strikes a circular pattern on a wooden panel covered with canvas using standard nails. In this way, he creates a structure that generates a game with perception. Try it once. How does the effect change when they move? What influence does light have on this?

And then there’s this big metal structure in the room. When you walk around it or look through it: How does it change your view of the exhibition space?

Oscar Tuazon’s installation “Numbers” literally reaches into the space. The iron plates and struts keep blocking our clear view of the rest of the room and the works on the walls as we walk around the sculpture. At the same time, new views of space and lines of sight open up that determine and influence our perception of space.

Audio by: Charlotte-Sophie Laege

Recording and editing in cooperation with the Making Media Space in the Digital Learning Lab at Bielefeld University.

In this space, stillness and movement, lightness and heaviness meet and make the tense moment in between palpable. Tuazon’s “Erector” pushes its raw, massive wooden beams up from the floor. In keeping with the Latin word “erectus,” he powerfully straightens up and stretches toward Alexander Calder’s “Mobile” on the ceiling. With this one, on the other hand, the lightness of a breeze is enough to set the colored iron parts in motion. They are only loosely connected by wires, which is why the balance of forces between the parts can quickly be dissolved and set into a spontaneous, undirected dance. The movement is designed in such a way that it always brings its components back into the quiet balance of weight and counterweight over time. But they remain mobile, “mobile” as it is called in French. Both works use the play between physical forces to draw images in space. When Calder’s “Mobile” is in motion, you can observe how the color surfaces slowly reposition themselves in relation to each other and create other impressions. It’s all a matter of perspective ( which you can also influence yourself). If you move around the room while keeping an eye on the mobile and Tuazon’s “Erector”, you can see how other shapes become visible depending on the angle of view.

“Erector” – verb or noun?

In addition to the meaning of “erector” already mentioned, Tuazon’s work title could also refer to the English noun “erector.” This means “builder” and would thus refer to Tuazon himself and the craft processes as part of his artistic creation.

Not everyone has a Calder, but many have a Mobile

Alexander Calder had not actually given names to his suspended, finely balanced constructions. He didn’t want to influence what people saw in them. However, when French artist Marcel Duchamp saw them, he referred to them as “mobiles” – from the French “mobile,” which means “movable” in German. The name caught on not only in the art world, but also, for example, for moving toys hanging from the ceiling, such as those found in many children’s rooms.

Audio by: Nadine Kleinken

Recording and editing in cooperation with the Making Media Space in the Digital Learning Lab at Bielefeld University.

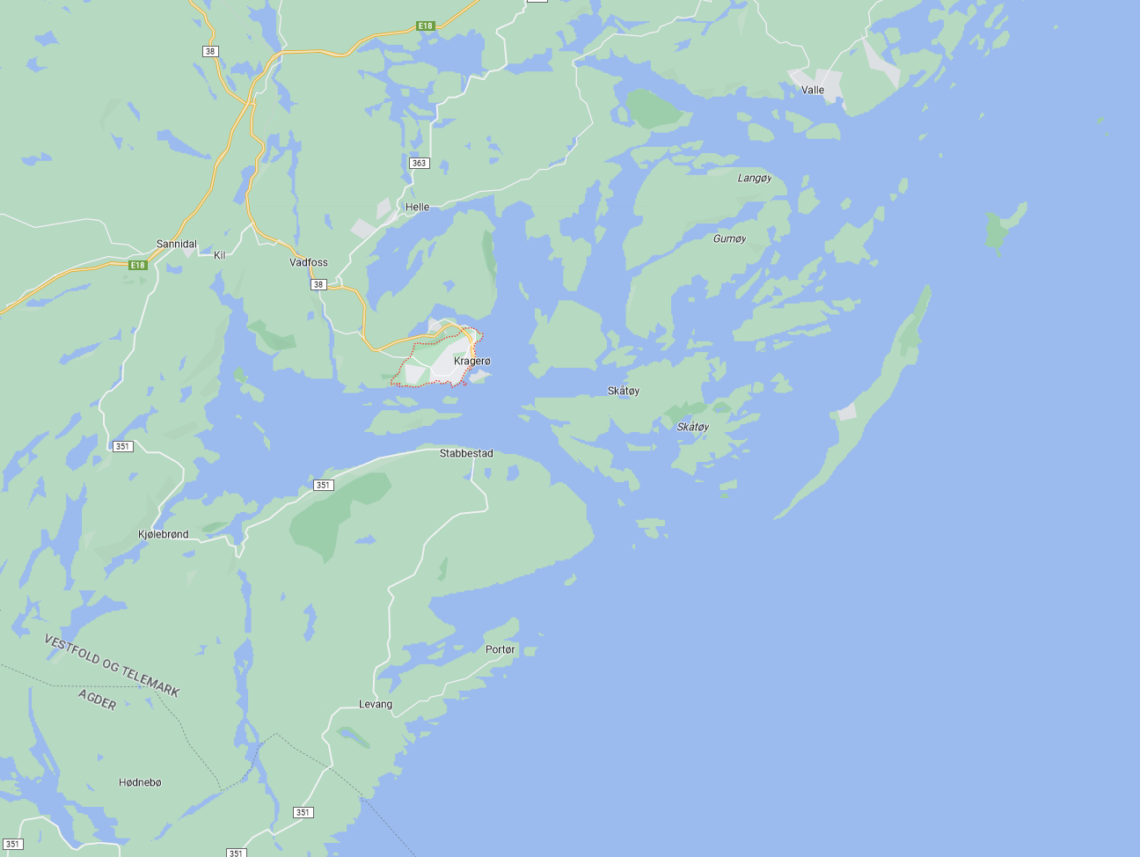

Detail from Google Maps

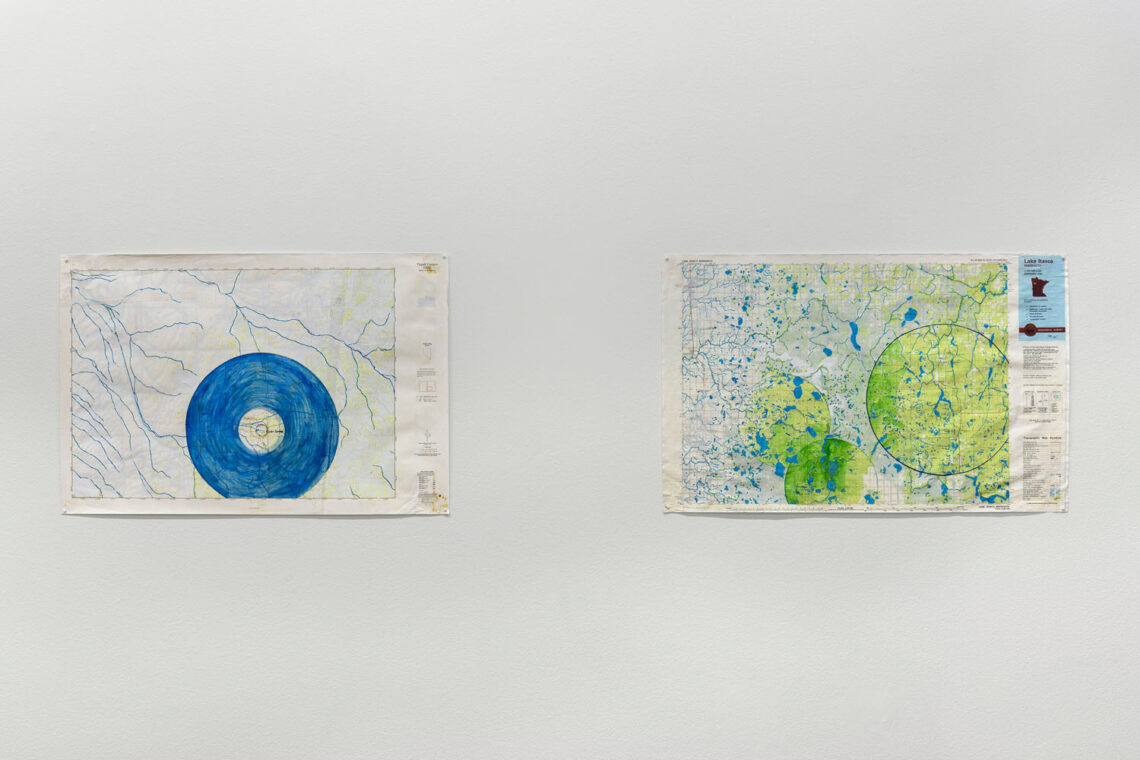

This exhibition space focuses on the relationship between man and nature: from virtually untouched nature to living in harmony with it to its domination by man.

Oscar Tuazon’s watercolors depict momentary sketches of landscapes that capture his impressions of unspoiled nature. Erich Heckel’s “Red Houses” from 1908, on the other hand, deals with the human settlement of nature. The houses belong to the fishing village of Dangast on the Jade Bay, but the color intensity does not correspond to reality. It reflects his emotional perception. It’s all about feelings! Heckel applied the colors spontaneously and combined them into simple two-dimensional forms.

Like Heckel’s “Red Houses”, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s painting “View into the Tobel” does not show a lifelike depiction of the surroundings. Kirchner develops forms from colored surfaces. With their idiosyncratic colorfulness, the artist expressed how he experienced the mountains. What do you think? How did Ernst Ludwig Kirchner experience nature? Which parts of the picture seem rather wild to you, which ones rather calm?

Edvard Munch’s “Village Street in Kragerø” shows us the everyday life of the people in the southern Norwegian coastal village at the beginning of the 20th century. You might think so. But there is much more in this picture! We can guess how people dealt with the environment back then, how they adapted. The dirt road is literally wedged in rocks – here nature dictates how people can live.

By the way, Edvard Munch is himself in the picture on the front left. How does he present himself in this scene? Is he one of them?

Now take a look at the two large photographs of a hedge. Impenetrable, like a green wall. Here a piece of nature was formed by man. Martin Brockhoff took these photos. The hedge can be seen here in its original size.

What are such hedges for? Properties and private gardens are thus delimited from the outside. “You can’t get in here,” they signal to us.

But that is not all. Have you noticed that you can also perceive these hedges simply as abstract images?

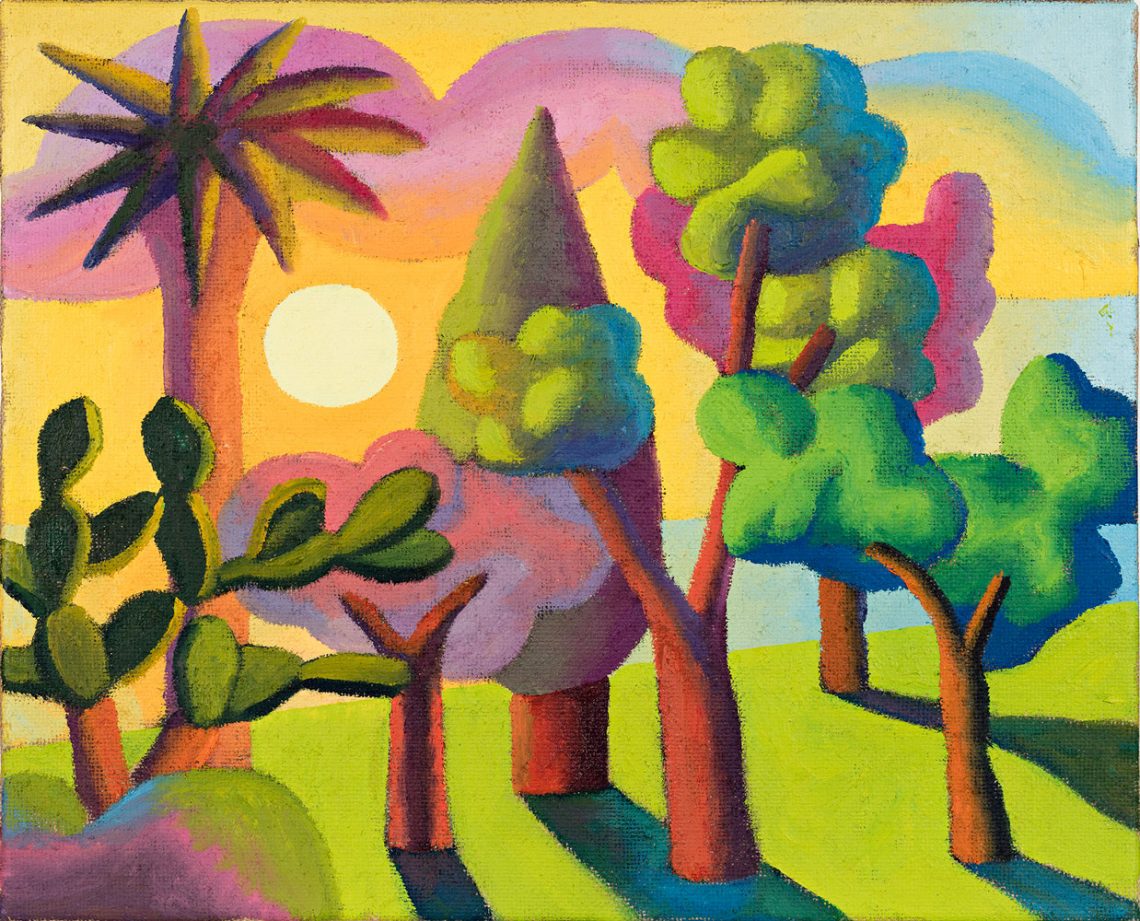

Now look at the almost square painting with its bright green and yellow tones. A forest. And what a one! Certainly not easy to get through here either. In the middle of it Bruno Krauskopf has painted a lonely cottage.

Here it is interesting to look at the year of creation: 1917, in the middle of the First World War. Perhaps the artist, who had also been a soldier, longed for a secluded life as a hermit, in harmony with nature.

Audio by: Nadine Kleinken

Recording and editing in cooperation with the Making Media Space in the Digital Learning Lab at Bielefeld University.

What do we need? As a society and as an individual? Connected with this leading question of the exhibition is the question of the necessary circumstances and conditions for the fulfillment of our needs.

The Peruvian-born artist Teresa Burga is today considered an important pioneer of Pop Art and Conceptual Art in Latin America. Both art forms emerged in the 1960s. Teresa Burga was practically unknown for a long time. Fortunately, that has changed in the meantime. We are particularly pleased that her work “Untitled (Bar)” has recently become part of the Kunsthalle’s collection.

In a 2019 interview, Burga said:

“I’ve always been interested, wherever I’ve been, in looking closely and seeing how and under what conditions women live.”

In her 1966 work “Untitled (Bar),” she observes closely: it’s a scene she saw on a trip to Paris. Several women in a bar. The 333 is perhaps the house number of a Parisian entertainment venue in the same neighborhood as the Moulin Rouge. The women are sex workers. Maybe they are waiting for customers. Or they recover.

How do the women affect you? Does the architecture protect them? Or do they seem caged in? What is their status in society? On the left side of the picture Burga works in photographs that show mainly men.

And then there are the Spanish words “Hoy” and “funcion” painted on the picture. The literal translation is “today” and “function”. “Funcion” can also mean “task, activity”. Or else “performance”.

What are these two words in the picture all about? Does this mean the “function today” of the women portrayed – or perhaps the program of events in the bar, i.e. the “performance today”?

What the bar in Teresa Burga’s painting cannot be, Oscar Tuazon’s work could be – a shelter. “I Put Food on the Table” – in German: “Ich Bringe das Essen auf den Tisch”. – resembles a self-built architecture.

If this construction were located in the Kunsthalle’s sculpture park, it would probably be inhabited pretty quickly. With the covered cave, it could provide us shelter from rain or fierce sun. We might as well use the raised platform to enjoy the warm rays of the sun. Or use it as a place for meeting and exchange.

So it is quite changeable and adaptable object. What it is depends entirely on us, our creativity and our needs.

What does “Remember this House” have to do with the other works?

Like Teresa Burga, Monica Bonvicini points to social injustices. The traces of the heavy chains remind of captivity. Bonvicini refers to the title of James Baldwin’s unpublished manuscript by writing “Remember this House.” In it, he wanted to tell the story of U.S. freedom fighters and ask whether racism had been overcome in the U.S. of the 1980s. For that, he also wanted to talk to the children of Malcom X, Martin Luther King Jr. and Medgar Evers are looking for.

Audio by: Matthias Albrecht

Recording and editing in cooperation with the Making Media Space in the Digital Learning Lab at Bielefeld University.

Gallerie